Facts CIRC

Annually, 80 projects are run at ANS leading to 6,000 over night stays across 500—600 researchers and students. CIRC with its 40 researchers belongs to the Department of Ecology and Environmental Science at Umeå University.

Image: Tomas Utsi

FEATURE In the sensitive mountain region, climate change can be seen with your bare eyes. The research station in Abisko hence has visiting researchers from all over the world. One of the operations carrying out climate studies in the Swedish mountains is the Climate Impacts Research Centre (CIRC) at Umeå University.

Abisko Scientific Research Station (ANS) is located 690 kilometres northwest of Umeå. About 40 kilometres east of the Norwegian border. And a ten-hour train journey from Umeå.

"People sometimes ask if it isn't lonely in Abisko. But Abisko and its surroundings is very popular among tourists and researchers, particularly in summer during which it really flourishes," says Jan Karlsson, director of the Climate Impacts Research Centre (CIRC).

Jan Karlsson director of the Climate Impacts Research Centre, CIRC, in Abisko.

PhotoTomas UtsiAnd he has had plenty of time to experience Abisko as he has made his entire career here. From 1998 as a doctoral student and later as professor and director of CIRC. Nowadays, he spends a few days per month here, and the rest in Umeå.

The person holding the fort in Abisko is instead project coordinator Keith Larson from the US. Since September 2013, Keith Larson and his family have lived all-year round at ANS.

Keith Larson’s task as project coordinator is to run the day to day business at CIRC and help researchers who come to Abisko. But he also has a few research projects on the go, one being the Nuolja research trail.

PhotoMattias PetterssonAnd according to Keith Larson, Abisko has a lot to offer also to researchers outside of CIRC.

"We have great labs and equipment. You can come here to carry out research, but also to work on your grant proposal or your paper. All the while, you get a change of scenery and can enjoy skiing or spotting the Northern Lights. And there's no queue to the labs. Just get in touch!" says Keith Larson in a welcoming tone from his office at ANS.

ANS is run by the Swedish Polar Research Secretariat and CIRC is the only tenant with researchers here all year round. Groups from other institutions come and go. The station has been extended on a number of occasions and the decorations remind you of the yellow and brown Swedish 1960s. The corridors are narrow and take you like a labyrinth in various directions.

At the visit, the building seems to lie dormant and the summer rush has still not quite kicked off. Many of the researchers are also doing fieldwork.

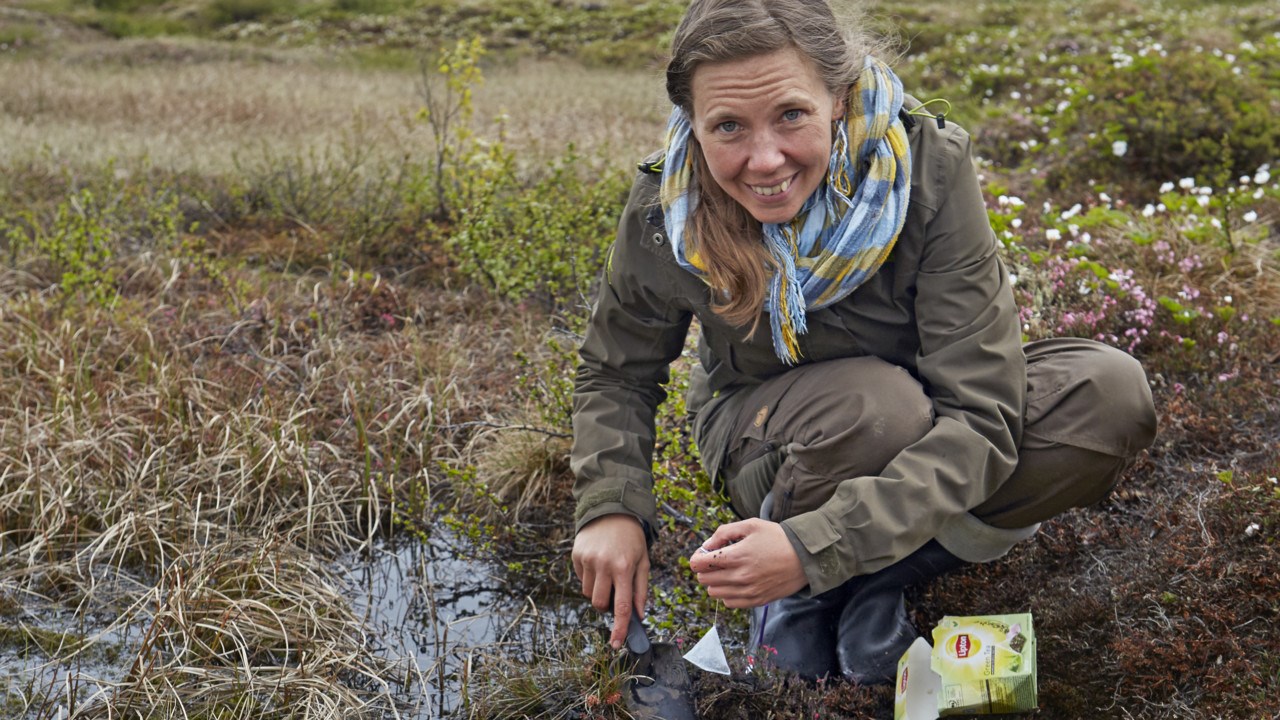

One of them is ecologist Judith Sarneel with her project Teatime 4 Science. She came to Sweden from the Netherlands four years ago to conduct research. This autumn, she is even teaching the new course Arctic Ecosystems in Abisko.

An advantage with Abisko is that everything is so well-organised. Equipment, car and lab can be rented from the station and nature is right on your doorstep.

"The landscape around Abisko gives lots of opportunities to study climatic variation, you only have to go to the next valley to find another precipitation zone," says Judith Sarneel.

Judith Sarneel, researcher at the Department of Ecology and Environmental Science and Climate Impacts Research Centre. On the picture, she is visiting Abisko Scientific Research Station (ANS) in Abisko for field experiments. Here, she is burying teabags in a research project to measure the level of decomposition after three months.

PhotoTomas UtsiWe are on our way out to the Storflaket mire. It is a rather chilly day with heavy grey clouds. The purpose of the excursion is to bury tea bags that Judith Sarneel three months later will dig up to measure the degree of decomposition.

The same mire is also regularly used by other researchers, particularly for permafrost studies. To the detriment of berry pickers perhaps. Because the field is full of cloud berry plants in full bloom that will later turn into the golden cloudberry — at least the female flowers, we find out.

Annually, 80 projects are run at ANS leading to 6,000 over night stays across 500—600 researchers and students. CIRC with its 40 researchers belongs to the Department of Ecology and Environmental Science at Umeå University.

This late in June, the mosquitoes have just arrived, but not in full attack mode yet. Spring had been cold and insects few, leading to delayed pollination of plants. The remaining patches of snow on the mountain are hence unusually thick causing trouble for some researchers with field sites on high altitudes. One of them is Maja Sundqvist who has had to spend many extra hours just reaching her field site resulting in not being able to meet up with us at all.

Sylvain Monteux, doctoral student at the Department of Ecology and Environmental Science and Climate Impacts Research Centre. He is stationed at Abisko Scientific Research Station (ANS). Here, at Storflaket , a field outside of Abisko often used for studies by researchers at Abisko Scientific Research Centre.

PhotoTomas UtsiSylvain Monteux, doctoral student in ecology, on the other hand is not affected by the weather right now. He has lived in Abisko for three years and has already spent hours measuring the depth of the active layer between the permafrost and the ground surface in the field. Now, his research is in a stage of data analysis at the station before he takes off on holiday back home to France.

"I really like Abisko. Seasons shift a lot, which provides good opportunities to vary how we conduct our studies. And we have a really good time outside of working hours," he says when he takes a break in the sun together with research colleagues from other research institutes outside the station.

Keith, Sylvain and Judith are not the only ones who have travelled far to come to Abisko for their research. The fact is, a majority of visitors at ANS come from abroad. This is not least noticeable from all the signs in English posted all over the station. And in the break rooms we bump into researchers from Canada, the UK, Denmark and Germany.

This particular week, CIRC with the help of researchers are arranging a seminar series under the name Arctic Days in Abisko. But popular science lectures to the public is no one-off affair. CIRC researchers regularly spread climate research to an interested general public in Abisko as well as in Umeå.

Although, not only research takes place in Abisko — but education too. We followed Stig-Olof Holm, associate professor in ecology, with the help of nature guide Hassan Ridha, on an excursion to Kärkevagge valley west of Abisko. Together with 22 students from the Umeå University summer course Alpine Ecology.

Students in the summer course Alpine Ecology are intensely trying to capture a bumblebee. When captured, the species is determined and the insect is released.

PhotoIngrid Söderbergh"The course is based on two sessions of field studies in Abisko focusing on birds and alpine plants. Today, the students will be learning more about alpine bumblebees and the effects of grazing on flora and fauna," says Stig-Olof Holm whilst walking along footbridges across wetland up the flowering valley.

At the start of the two-day stay Čuonjávággi (Tjuonavagge) — the Lapponian Gate — was hard to spot behind thick clouds, but ready for our departure, the well-known gate showed its splendour together with the midnight sun.

Text and translation: Anna Lawrence

Top photo: Thomas Utsi

This article was first published in the magazine Aktum no. 3 2017.

See more photos from Abisko Scientific Research Station and CIRC.

Image Ive Van Krunkelsven

The library at ANS is looking out on the quiet Lake Torne träsk. Here, one can peacefully work among titles such as A Changing Arctic Climate; Geomorphology, Environment and Man; and The Permafrost Environment.

Image Tomas Utsi

Hannah Rosenzweig and Lara Schmitt come from Germany and are doing their internship in Keith Larson's phenology project. They have, together with Hassan Ridha, been very helpful in measuring the snow coverage, analysing soil moisture and registering plant development on the Nuolja research trail.

Image Tomas Utsi

Student Moa Pettersson has captured a Bombus polaris bumblebee on the way up to Kärkevagge and shows it to Stig-Olof Holm and Hassan Ridha.

Image Anna Lawrence

Inauguration of Nuolja research trail in Abisko.

Image Tomas Utsi

Judith Sarneel, researcher at the Department of Ecology and Environmental Science and Climate Impacts Research Centre. She is visiting Abisko Scientific Research Station (ANS) in Abisko for field experiments. Here, she is burying teabags in a research project to measure the level of decomposition after three months. The temporary field of research is the mire Storflaket outside Abisko.

Image Tomas Utsi

Sylvain Monteux, doctoral student at the Department of Ecology and Environmental Science and Climate Impacts Research Centre. He is stationed at Abisko Scientific Research Station (ANS). Here, at Storflaket, a field outside of Abisko often used for studies by researchers at ANS. Sylvain Monteux studies permafrost and its correlation with microbes.

Image Tomas Utsi

The library at ANS is looking out on the quiet Lake Torne träsk. Here, one can peacefully work among titles such as A Changing Arctic Climate; Geomorphology, Environment and Man; and The Permafrost Environment.

Hannah Rosenzweig and Lara Schmitt come from Germany and are doing their internship in Keith Larson's phenology project. They have, together with Hassan Ridha, been very helpful in measuring the snow coverage, analysing soil moisture and registering plant development on the Nuolja research trail.

Student Moa Pettersson has captured a Bombus polaris bumblebee on the way up to Kärkevagge and shows it to Stig-Olof Holm and Hassan Ridha.

Inauguration of Nuolja research trail in Abisko.

Judith Sarneel, researcher at the Department of Ecology and Environmental Science and Climate Impacts Research Centre. She is visiting Abisko Scientific Research Station (ANS) in Abisko for field experiments. Here, she is burying teabags in a research project to measure the level of decomposition after three months. The temporary field of research is the mire Storflaket outside Abisko.

Sylvain Monteux, doctoral student at the Department of Ecology and Environmental Science and Climate Impacts Research Centre. He is stationed at Abisko Scientific Research Station (ANS). Here, at Storflaket, a field outside of Abisko often used for studies by researchers at ANS. Sylvain Monteux studies permafrost and its correlation with microbes.