Alumni Interview: From Newton to Apple - The physicist who shaped the iPhone

Camille Moussette, the pioneering PhD graduate from UID, is designing for hundreds of millions of people. This is his journey from struggling physicist to impactful designer at the heart of the Apple factory.

In the late 1980s, a young Camille Moussette navigated his radio-controlled cars down the streets of Montreal, Canada, with expert precision. In the evenings, him and his father used to tinker with the cars' engines in the basement. The young boy's fascination for mechanical things didn't stop at RC cars. Everything from computers to photo equipment caught his eye. His interest in how the world works, and the things in it, would not wane over time. In fact, he would later influence how things, namely Apple products, would be experienced by hundreds of millions of users across the globe.

In his role as lead interaction designer at Apple, Camille has a very clear idea of what his design vision entails. The functionalities that he creates for products should offer a 'human touch'. The word touch should be taken quite literally here. Camille's field of interaction design is known as haptics, which is basically designing for touch, instead of vision or hearing. The obvious example being the vibration you experience in your pocket when your phone rings, instead of the actual audible ringtone.

The Photo Club Epiphany

Camille's path towards the design profession was not a straight one. While new technologies always interested him as a child - from cars to cameras - his fascination veered towards the physical machinery of the objects, rather than the aesthetics or the user experience. It was also his interest in physics that would inspire his first endeavor into the world of academia, at Sherbrook University in Canada.

I really liked the experimental aspects of physics, building stuff and trying things out in the real world

"I really liked the experimental aspects of physics, building stuff and trying things out in the real world. That's what made me do my first bachelor in physics, with a focus in microelectronics. Although, I would soon learn that all aspects of academic physics were perhaps not for me. I barely passed my final quantum physics exam and that's probably when I realized that I wasn't cut for hard science, at least not quantum physics and advanced mathematics. My peers were so much better than I, and to be honest it's really not comfortable for my brain to grapple with mathematics on that level".

Camille Moussette during his time at UID.

ImagePeder Fällefors, Andreas NilssonCamille's struggles with mathematics pushed open another door. When he wasn't wrecking his brain trying to grasp the complexities of theoretical physics, he increasingly found refuge at the university photo club that he helped direct and run over three years. The photo club was not only a sanctuary from the rigidity of hard science. Here, he could express his artistic side through photography. As time went by, the photo club seemed to command more and more of his time. He would spend late evenings developing black and white photographs using traditional methods as well as writing software for him and his peers to be able to scan and retouch images digitally.

As his time at Sherbrooke University drew to a close, Camille had realized that he would never become that stereotypical scientist with Einstein-esque hair, pondering mathematical theorems in closed chambers. The photo club had awakened a desire to combine the nuts and bolts of physics with his more practical, yet creative side. Hence, industrial design.

Making the Digital Physical

Camille's first foray into design brought him back to his native Montreal where he studied the bachelor programme in industrial design. While it was an inspirational time, his desire to combine technology and design wasn't quite met. More tabletops than laptops on the curriculum, so to speak. It was not until his final degree project that he could start exploring what would later become his niche as a professional designer.

It was the first time that I combined electronics and design, and where the interaction and the user experience was more important than the physical embodiment of the thing

"I was always more into the intersect between design and technology so I ended up doing a grad project where I developed a watch notification functionality. The product or service I created was placed under the watch and it vibrated to let you know that your phone was ringing. That project was a real eye opener for me. It was the first time that I combined electronics and design, and where the interaction and the user experience was more important than the physical embodiment of the thing. It was a natural fit for me considering my background".

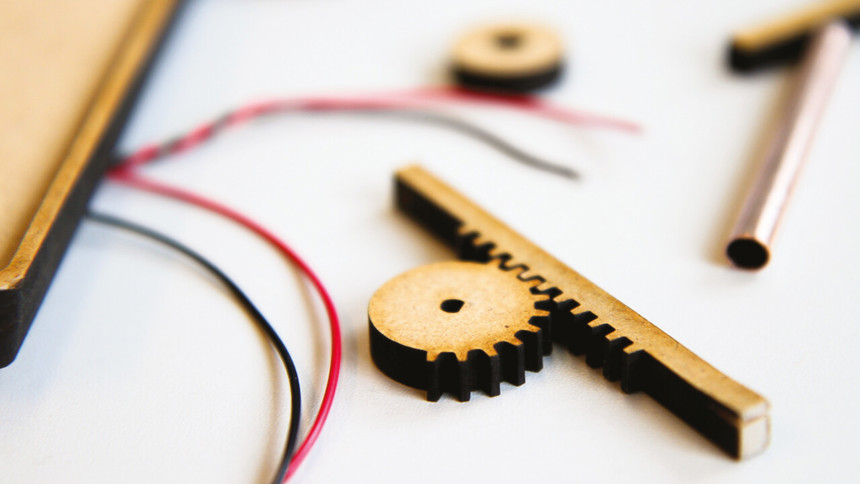

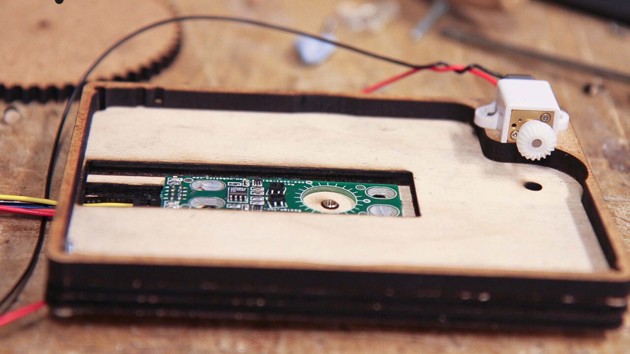

Experimental prototype from Camille's PhD thesis, 'Simple Haptics'.

ImageCamille Moussette"After that experience I knew that I wanted to help make digital products tangible in some way. I wanted them to be more dynamic and sort of come alive, become useful and meaningful when you used them. But I also knew that my skills as a designer, especially understanding the user and the process, wasn't enough to do what I wanted to do."

I knew that I wanted to help make digital products tangible in some way

In the third year of his bachelor in Montreal, Camille visited Finland as an exchange student. He had always been curious about the Nordic countries and after a year at Oulu University he had fallen in love with the way of life in Northern Scandinavia. Oulu sits just across the Bothnian Bay from Umeå and when Camille was looking for a place to do his master's in interaction design in 2007, Umeå Institute of Design seemed like a good fit. He ended up staying for eight years.

Designing for Touch

The Master's Programme in Interaction Design at Umeå Institute of Design helped Camille bridge the gap between technology and human behavior, learning how to give shape to that very relation. All through his master's, as well as the PhD programme that he would later pioneer at UID, Camille was focused on haptics.

From the time of his first grad project in Montreal he had always felt that designing for touch was an unexploited field. As he approached his PhD, he was certain that he had found a blind spot in the way communication devices were designed. For whatever reason, this design medium had been either overlooked or deliberately brushed to the side by designers and companies in the tech industry.

Camille Moussette 'nailing' his thesis upon completing his PhD defense.

ImagePeder Fällefors"Often in design, we tend to rely on the latest technical development and industry trends to tell us in which direction we should go, instead of just experimenting. I made it my mission during my PhD at UID to just keep on playing around with different prototypes, exploring how haptics could be used for a lot of different design purposes. The more I got into it, the more excited I got."

Within a couple months I too had moved to California, starting a new job at Apple

"At the end of my PhD, I was looking for senior academic professionals to be on my evaluation board and I contacted a professor from Yale whom I had collaborated with before. He said he would love to do it but that unfortunately he had just left academia for a new position at Apple. He invited me for a job interview as soon as I had finished my PhD. Within a couple months I too had moved to California, starting a new job at Apple."

Camille in the Apple Factory

When Camille first arrived at the Apple headquarters it was a bit like Charlie walking into the chocolate factory. For a budding interaction designer, opportunities seemed endless. He initially joined a prototyping engineering team, but also worked closely with the industrial design group on new product experiences. Later on, he transferred to the design team to explore hardware interaction design. Today, the design team at Apple consists of over a hundred people, working on everything from traditional product design, to interaction design, to interface design. It is a place where ideas quickly can become reality, where the final products end up in the hands of hundreds of millions of people, across cultures and continents.

Throughout his career in design, and before really, Camille has stayed true to his core design methodology. And that is simply to build stuff, and then build again. He believes that only through the process of making hardware sketches, prototypes and testing models, can you get close to the real thing, the end user experience. This seems to be true whether you are in the design studio at Apple headquarters or in your dad's basement in Montreal.

ImageMostphotos

"The most rewarding part of the design process, for me, is when you get creative and come up with exciting yet incomplete ideas, and just build stuff to learn. In my day to day, I tend to build a lot of things because when you have an idea, you can't get close to the actual experience until you engage with it in a physical and visceral way, from the point of the user. Engaging intellectually is simply not enough."

When you have an idea, you can't get close to the actual experience until you engage with it in a physical and visceral way

"At times we have these moments when we're playing with prototypes and it feels special, magical and humanely satisfying. These are insights that no amount of rationalizing or intellectual exercise can offer. You have to craft something real into the world and when it works it speaks back to you, and that moment is beautiful", says Camille Moussette.

Making a Mark

When you are a cog in the global Apple machinery, it means that you are always designing for an audience of millions. The sheer impact in numbers that comes with being part of the world's leading tech company is mind-boggling. When it comes to taking an idea and manufacturing it at scale, few can compete. This should add a bit of pressure to the design experience, one would imagine.

Being part of this massive machinery, you feel a great responsibility to do your homework

"Being part of this massive machinery, you feel a great responsibility to do your homework, no doubt. If they say go, they're going to manufacture hundreds of thousand of phones a day containing that very thing that you first thought was interesting and then helped develop. It's scary and exciting at the same time."

Camille Moussette during a visit to the UID18 Design Talks & Degree Show.

ImagePeder FälleforsSome of the design applications that carry Camille's fingerprints are the 'Taptic Engine' in the AppleWatch, the haptic 'Home Button' and the 'Attention Aware' features with 'FaceID' on the newer iPhones.

"These design solutions all relate to some aspect of my first grad project in Montreal where I made this vibrating watch to replace the phone's ringtone. It's all about being considerate, really. Looking at the FaceID functionality on the current iPhones for example, when it rings now and identifies a face it will reduce the volume of the ringtone as well as the vibrating haptics."

...kind of like someone tapping you on the shoulder instead of shaking you

"The haptic experiences that we use today are much more subtle and refined. We want to create very precise taps, instead of overwhelming and stress-inducing vibrations. That gives us the ability to be more delicate and gentle, kind of like someone tapping you on the shoulder instead of shaking you."

Quite simply, a human touch.