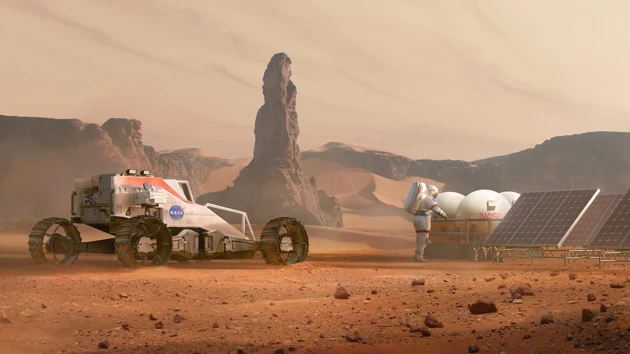

Joakim Englander's UID grad project, carried out in collaboration with NASA, is a lightweight, single-astronaut transport designed for short exploration missions on the Martian surface.

From sketches to screens: How Joakim Englander is shaping the future of gaming

When Joakim Englander graduated from the BFA Programme in Industrial Design, he stepped into the gaming industry with a portfolio that spoke volumes, both in concept art and industrial design. Today, he’s working out of London as a Concept Designer at DICE, the Stockholm-based studio behind the iconic Battlefield franchise, where he’s helping to shape the future of interactive entertainment.

But his journey began long before high-budget, blockbuster-style game development. It started with a clear vision.

“I knew I wanted to work in the entertainment industry when I applied to UID,” Joakim recalls. “I chose the school mainly for its robust industrial design programme.”

Designing for reality, and beyond

At UID, Joakim found more than just technical training. He found a design philosophy grounded in real-world application. “The exposure to real-world design briefs and collaborations with companies was invaluable,” he says. “The fundamentals – sketching, rendering, model building, and manufacturing techniques – are skills I still use every day.”

A pivotal moment came during his second-year internship, where he joined a small Stockholm-based game studio as a concept artist. “It was the first time I could put theory into practice,” he says. That hands-on experience would prove instrumental in launching his career.

Breaking into the industry

Joakim’s transition from student to professional was remarkably smooth. “I was lucky,” he admits. “After graduating, I was contacted to support the pre-production of a game as a concept artist.” He credits his strong portfolio for opening that door, one that showcased not only his artistic flair but also his grounding in industrial design.

Today, at DICE, Joakim is one of just two concept designers responsible for the hardware of Battlefield. That means gadgets, vehicles, weapons, anything with a hard surface that players can interact with.

A snapshot of Joakim Englander's world building.

“The challenge is designing things that don’t exist, that might not even make sense, but still need to feel plausible, and fun,” he explains. “With the level of graphical fidelity in games today, everything has to feel like it could be real.”

Working on an AAA title – a video game produced or distributed by a major publisher – brings its own set of pressures. Designs must not only be imaginative and technically sound but also meet the expectations of millions of players worldwide.

A process rooted in improvisation

Joakim’s design process is a blend of rigour and invention. It begins with a brief, often from an art director or game designer, and quickly moves into research. “I collect references, articles, videos, and arrange them in ‘PureRef’,” he says. “That becomes my visual compass.”

Joakim Englander during his 3D animation design process.

From there, he toggles between 2D and 3D tools – Photoshop, Blender, Plasticity –depending on the task. “Using 3D early helps get the scale right,” he notes. “For complex designs, I can even rig and animate them in the mock-up phase.”

But the real work happens in the back-and-forth: iterating with art directors, game designers, animators, and VFX artists to ensure the design not only looks good but plays well.

While his work doesn’t result in physical products, Joakim is acutely aware of the cultural impact of game design. “Games have historically leaned on stereotypical archetypes,” he says. “As a concept designer, I have a responsibility to avoid reinforcing those. It means looking critically at my work and being intentional about what I create.”

Life beyond the screen

Outside of work, Joakim’s world revolves around family. “Having children lets you experience things for the first time again through their eyes,” he says. When time allows, he explores London’s museums and exhibitions, always eager to learn something new.

He also carves out time for personal projects, design work that’s just for him. “It’s a way to stay creatively fulfilled without the constraints of a client brief.”

If he could go back to his UID days, Joakim knows exactly what he’d say: “Practise your fundamentals even more. Tools change, but if your foundation is solid – sketching and design thinking – you’ll be alright.”

The power of curiosity

Asked what his design superpower might be, Joakim doesn’t hesitate. “Curiosity,” he says. “I’ve always been interested in different subjects. That curiosity helps me find interesting angles on all kinds of tasks.”

And when it’s time to get into the zone? “Ambient music, mostly. For ecample Carbon Based Lifeforms, Solar Fields, Stellardrone. But if there’s a tight deadline, I’ll turn on some Black or Death Metal. It gets the job done.”

When he thinks of UID, two word spring to mind. “Camaraderie and friendship,” he says. “All those late nights in the digital drawing room, everyone pushing the envelope. It was tough, but we went through it together.”