Seda Özçetin presenting her research during the DCODE Summer School hosted by Umeå Institute of Design.

Unpacking the “biggest lie on the internet”

In a rushed moment, most of us have checked the “I Agree” box on our phones within seconds. But what did we agree to? Was it actually designed for us no to ask that very question? In a sense, yes. Seda Özçetin, PhD student at Umeå Institute of Design, explores the intricate networks of actors beyond the ticked boxes.

The phrase “the biggest lie on the internet” was coined by Jonathan A. Obar and Anne Oeldorf-Hirsch in a paper from 2016. Through an empirical investigation, the researchers reveal that the information overload built into online terms of service (ToS) can get people to agree to just about anything. This is perhaps most strikingly illustrated in an example where 98% of participants missed a ‘gotcha clause’, essentially agreeing to provide their first-born child as payment for joining a social networking platform.

Seda Özçetin describes her own relationship with terms of service as almost “toxic”. As she uncovers more and more truths about the complex, underlying ecosystems of actors behind the checkboxes, she becomes equally annoyed and intrigued. Through her research, she hopes to lay bare motives and relationships within the elaborate networks of stakeholders on the other side of these digital contracts. Seda’s PhD project, carried out within the DCODE network, aims to provide transparency and accountability to the process, as well as give more agency to not only users, but to the planet itself.

“When we focus on our immediate interactions with terms of service online, such as the ‘I agree’ checkbox, we often frame the problem within the perspective of user-centered design where the goal is to make interactions frictionless, yet accessible. But we miss the point here, I believe. In practice, no matter how well-designed these interfaces are, it’s a lost battle considering the number of apps and digital services we use on daily basis, including the ongoing updates that are made. There’s simply no way to keep up. Instead, we need to look beyond the relationship between a person and an interface and move onto relations between a person and a broader network of more-than-human actors with their own agencies”, says Seda Özçetin.

In an exploration recently published in the Journal of Human-computer Interaction’s special issue, Seda Özçetin and her co-author Dr. Heather Wiltse cast a spotlight on the intriguing concept of ‘posthumanist HCI and the more-than-human turn in design’. The authors delve into the elaborate labyrinth of these relationships through a unique practice they’ve coined ‘revealing design’. This practice is a triptych of design manoeuvres, each with its own distinct purpose and impact. One such action involves charting the complex relationships as outlined in the terms of service agreements. This mapping serves as a compass, guiding us through the labyrinth of connections that shape our digital world.

Mapping the invisible: A journey into the forests of Umeå

To further untangle the web of different stakeholders hidden behind the ticked boxes, Seda devised an unusual mapping method. She ventured into nature to help us see the proverbial forest, as well as the trees. On a crisp spring morning, Seda brought her sister Şeyda, co-founder and art director of their design studio Hamide, for an excursion into the forest on the outskirts of Umeå. To help her get a different perspective of the detailed workings that make up terms of service, she began mapping out core systems of actors, as each tree got to represent a company or an institution with a vested interest.

A unique experiment unfolded over three workdays. As they turned one of her 2D relational maps that illustrates the entangled terms of service ecosystem, what she calls a ToSsphere, into a 3D spatial map, the two sisters, who had previously admired the forest from its defined paths, found themselves immersed in its depths, engaging with it in a way they never had before.

Seda created a 3D spatial map using trees as actors to map out the complex network of actors behind online terms of service.

“The mapping was an intense exercise. Using trees as actors, policies had to be hung one by one, a task that demanded a significant investment of time and energy. While challenging and stressful, the process eventually led to a profound connection with the environment. We found ourselves attuned to the materials we were working with, as well as the surrounding elements - the trees, the sun, the wind, and even the spiders”, says Seda Özçetin.

From terms to trees: A shift towards eco-social contracts

As the hours passed, marked by shifting lights, the chill on their arms, and the quieting of the birds, they began to notice something striking. While they were deeply engaged with manifesting the webs involved actors, and deciding which tree could represent which third-party service, they realized what was missing from these documents – nature and its resources. Despite the digital facade, these services are heavily reliant on tangible resources such as minerals, energy, and land. Yet, there was no mention of these elements, raising questions about their agency and the accountability of these services for their impact on nature.

“This revelation sparked a shift in perspective, leading to a deeper exploration of how we can recognize nature’s agency. The insight has since signaled a further focus in my research towards agreements that consider both ecology and society, rather than just agreements between people”, says Seda Özçetin

Seda’s sonic revolution: A new dimension to online data handling

In an unexpected move, Seda is currently pioneering the sonification of ToS interactions, infusing auditory elements into the experience. Traditionally, these policies and their extensions are interacted with in the seclusion of our personal devices, a silent exchange. This solitary and mute interaction perpetuates the notion that it’s up to us individually to understand and form opinions on how our online data should be handled. Seda, however, is poised to challenge this belief. The question at hand: what transpires when we introduce a sonic dimension to these interactions, effectively shifting this private encounter into the public sphere?

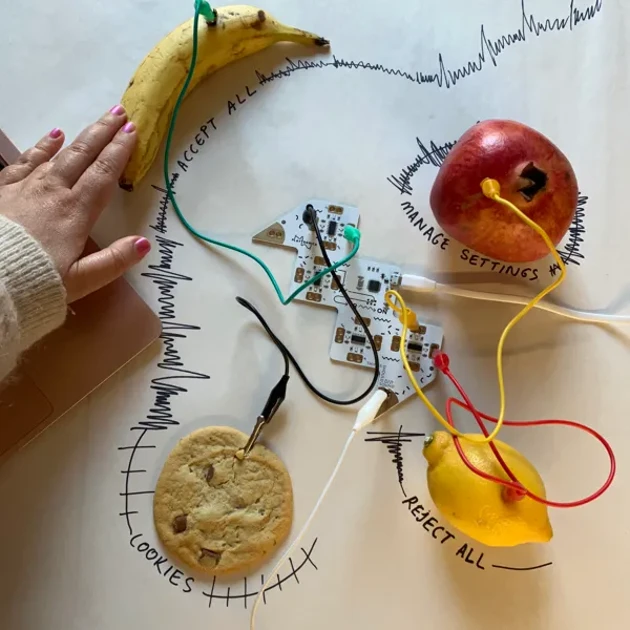

Seda has acquired Playtronica MIDI devices and is experimenting with how to incorporate the experience of sound into ToS interactions.

“My overall goal here is to create a space of inquiry around how our relations to data-intensive things are mediated. Each exploration expands this space, while also presenting some key findings that could help us imagine alternatives. I think my work, if it reaches the right audiences, could ignite both bottom-up and top-down actions”, says Seda Özçetin.

Seda's article 'Terms of entanglement: a posthumanist reading of Terms of Service' was published in a recent issue of the journal 'Human–Computer Interaction'.

Article abstract: Contemporary connected things entail ongoing relations between producers, end users, and other actors characterized by ongoing updates and production of data about and through use. These relations are currently governed by Terms of Service (ToS) and related policy documents, which are known to be mostly ignored beyond the required interaction of ticking a box to indicate consent. This seems to be a symptom of failure to design for effectively mediating ongoing relations among multiple stakeholders involving multiple forms of value generation. In this paper, we use ToS as an entrance point to explore design practices for democratic data governance. Drawing on posthuman perspectives, we make three posthuman design moves exploring entanglements, decentering, and co-performance in relation to Terms of Service. Through these explorations we begin to sketch a space for design to engage with democratic data governance through a practice of what we call revealing design that is aimed at meaningfully making visible these complex networked relations in actionable ways. This approach is meant to open alternative possible trajectories that could be explored for design to enable genuine democratic data governance.