Image: Johanna Nordström

Image: Johanna Nordström

FEATURE Anorexia nervosa is the psychiatric diagnosis with the highest mortality rate. At the same time, it is one of the most difficult to treat. There are no effective medications, and those affected find themselves in a cruel catch-22 – one of the most important factors for treatment to work is weight gain. At Umeå University, a multi-front battle is underway to combat the disease: research on mice, mind, and molecules.

"This might feel like the research furthest removed from patients," says Olof Lagerlöf as Qiongxuan Lu takes Petri dishes out of the refrigerator.

Olov Lagerlöf, Assistant Professor in Psychiatry at the Department of Clinical Sciences.

ImageJohanna NordströmOlof Lagerlöf is Assistant Professor in Psychiatry at the Department of Clinical Science and a resident physician at Norrland University Hospital. His lab conducts research on anorexia nervosa all the way from molecule to mind. In these Petri dishes, yeast is being cultivated – the same kind used for baking or brewing beer. The link to anorexia may seem far-fetched, but the goal is to identify genes worth studying further, and yeast happens to be an efficient test subject.

"We’re testing 8,000 different genes. Doing that with mice would be very impractical," explains Lagerlöf.

Self-starvation in religious or spiritual contexts has been documented since antiquity, but in the 19th century, the condition began to be described as a disease called anorexia nervosa. Today, three main criteria form the basis for diagnosis: a distorted body image, perceiving oneself as overweight; a drive to restrict food intake; and an extreme fear of eating food that could lead to weight gain.

Magnus Sjögren, Associate Professor in Psychiatry at the Department of Clinical Sciences.

ImageMagnus Sjögren"A person with anorexia feels a constant need to control themselves," says Magnus Sjögren, Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the Department of Clinical Science. He is also Head of the National Highly Specialized Care Unit for Severe Eating Disorders in Sundsvall and has met many patients with severe anorexia.

"They mainly control their food intake, but after eating, there’s a strong need to get rid of what they’ve eaten, either by exercising to burn calories or by vomiting or using laxatives. And this isn’t just a little exercise; it can mean several hours a day, or even at night."

It’s hard to know how many people in Sweden suffer from anorexia. The National Board of Health and Welfare estimates about 200,000 people aged 15–60 have some form of eating disorder, with a likely hidden number. About 80% are women. Common types include binge eating disorder, bulimia, and unspecified eating disorders. Switching between types and having comorbidities like depression, anxiety, self-harm, or OCD is common.

Peter Asellus, Associate Professor in Psychiatry at the Department of Clinical Sciences.

ImageHans Karlsson"Anorexia can be a condition in and of itself, but it’s also possible that an eating disorder can be triggered by another illness. In depression, for example, it’s common to have a very negative self-image and reduced appetite. Something that might make you feel a little better is to stop eating, almost as a punishment. These are behaviors that can spiral out of control," says Peter Asellus, Associate Professor in Psychiatry and Senior Consultant Physician at Norrland University Hospital.

The more intense the illness, the more it affects life. In the short term, one might feel rewarded when meeting the demands of the disorder, but that rarely lasts. Magnus Sjögren describes how the illness eventually takes over patients’ lives and they become governed by the eating disorder. Behaviors that maintain the illness also become habits, making recovery harder if the illness has lasted a long time.

"I sometimes stick my neck out and call this an addiction. Just like smoking or substance abuse, there are aspects of eating disorders that resemble an addiction syndrome. These individuals return to the illness because it feels safe," says Magnus Sjögren.

Anorexia has the highest mortality rate among psychiatric diagnoses, somewhere between 5–10%. The cruel irony is that effective treatment requires weight gain.

"When someone loses weight to a harmful level, they become more rigid in their thinking, whether they have anorexia or not. Low body weight makes it hard to absorb information, and going through CBT for anorexia demands a lot. You need enough energy to listen to your therapist," says Olof Lagerlöf.

At the same time, it’s important to emphasize that many who suffer from anorexia recover or at least improve after treatment. Most agree to measures like meal plans or therapy. Treating comorbidities can also help indirectly with weight, even if that’s not the main focus.

"The key is to make patients feel better. If life improves first, maybe weight loss may no longer feel necessary. If that leads to weight gain later, it’s because they feel comfortable with it," says Peter Asellus.

At the national specialized care unit, Sjögren researches radically open dialectical behavior therapy, which shows promise in keeping patients in treatment longer and ensuring safety.

Unfortunately, it is common for patients with eating disorders to drop out of treatment

"Unfortunately, it’s common for patients with eating disorders, especially anorexia, to drop out of treatment. Finding approaches that feel right for them is crucial. We also influence thoughts and feelings during treatment, so patient safety is vital to prevent worsening or self-harm. This therapy seems safe," says Magnus Sjögren.

He has also launched the PROÄT study, which follows patients over time to identify recovery indicators and modifiable factors.

"Hopefully we can start identifying indicators of who will recover from treatment, and what factors are associated with recovery overall or faster recovery. At the same time, we hope to identify modifiable factors linked to recovery," says Sjögren.

Environmental and social factors matter when developing anorexia, but genetics play a role too – heritability can be up to 60%. Research also shows that the brain in anorexia patients reacts differently than in others.

The brain reacts with anxiety when consuming calories

"One connection that fails in the brain in people with anorexia is the one between anxiety areas and metabolism areas. The brain misinterprets biological signals and reacts with anxiety when consuming calories – as if something terrible is happening," explains Lagerlöf.

Similar mechanisms appear in animals. In Lagerlöf’s lab, mice given restricted food and access to a running wheel can develop anorexia-like behavior. They show self-induced starvation and excessive activity.

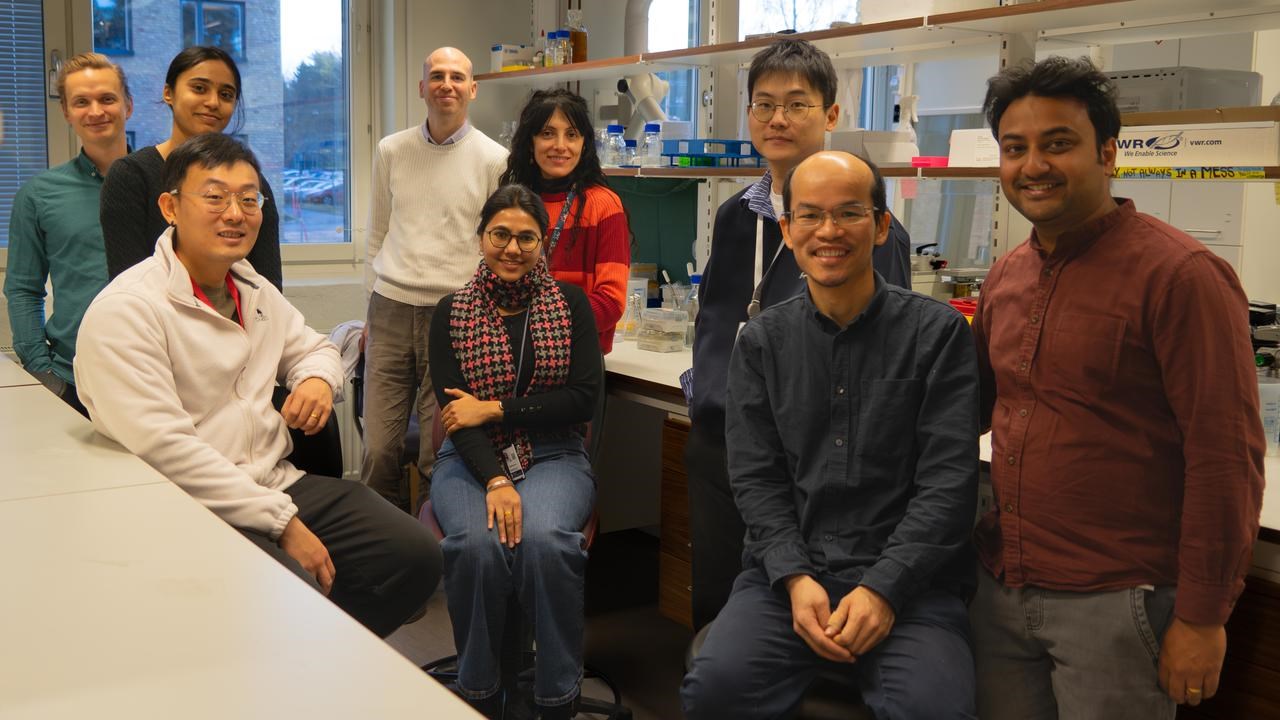

Manish Bhattacharjee studies braincells from mice in Olof Lagerlöf's lab.

ImageJohanna Nordström"If you only restrict food, weight stays stable. But if they also have a wheel, some mice eat even less and burn more energy. They seem to choose running over eating. Biology should save you, but here it seems to make things worse. And female adolescent mice are most at risk," says Lagerlöf.

Both Lagerlöf and Asellus argue that biological aspects of anorexia are understudied. Asellus researches thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency and its role in anorexia. Thiamine is essential for glucose metabolism in the brain; deficiency can cause brain damage. This might make not eating paradoxically protective.

It's hard to treat an eating disorder if there's no appetite

"Could lack of appetite be almost a protective mechanism? And could supplementing thiamine kickstart appetite? It’s hard to treat an eating disorder if there’s no appetite, but adding thiamine signals to the body that it’s safe to eat," says Asellus.

In Lagerlöf’s lab, the hope is to improve therapy, diagnostic markers, and enable precision medicine.

"In therapy, it’s important to understand how thoughts are affected by food, and what effect calories have on the brain in anorexia. If we also understand how brain connections are altered, we can image the brain and say: ‘Aha, you have this misconnection, so we treat it this way,’" says Lagerlöf.

In the lab, everyday yeast cells sit next to high-tech equipment worth millions. Among other things, the team uses it study how to image specific brain areas with great precision. Lagerlöf believes psychiatry’s future lies in targeting individual neural circuits rather than the whole brain.

The team at Lagerlöf Lab researches food intake from molecule to mind.

ImageJohanna Nordström"Medications affect the entire brain, making it hard to find specific targets – hence the side effects. But if we can pinpoint the link between neuron 1 and 2, if we know that’s what we need to target… Such treatments exist for some neurodegenerative conditions, but not yet in psychiatry. The principle is there, but it may be 10–20 years away," says Lagerlöf.

Hope remains that we can disarm the deadliest psychiatric diagnosis. And in mice, yeast, and brain cells, we may have found unexpected allies.