NEWS Whether bacteria compete or cooperate depends on subtle interactions, often studied using abstract mathematical models. Now, students at Umeå University have transformed this research into a computer game, making microbial dynamics visible and playable.

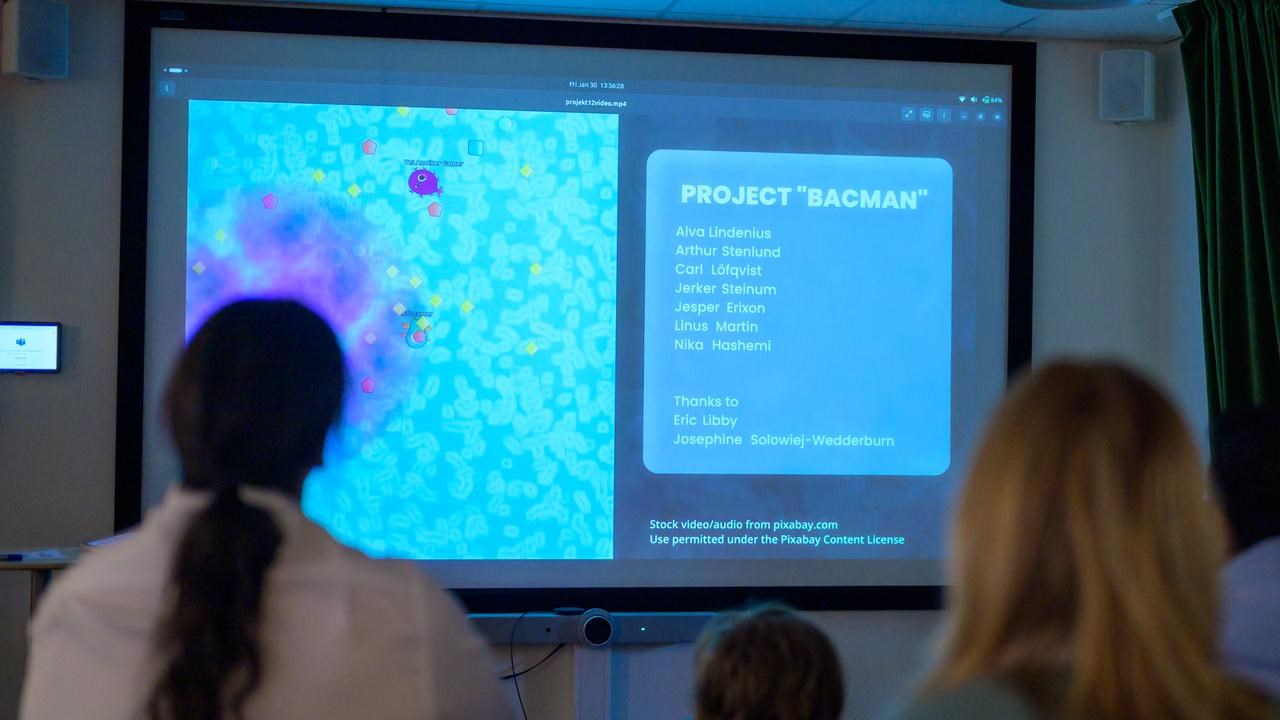

Researchers in IceLab test the BacMan game

Image Gabrielle BeansIn the microscopic world, bacteria often compete for nutrients and other essential molecules. At the same time, they can also cooperate, using by-products released by other bacteria in the same environment. Understanding when bacteria compete versus cooperate, and how they respond to their environment is the subject of research carried out by Josephine Solowiej-Wedderburn, postdoctoral fellow, and Eric Libby, associate professor, both affiliated with the Integrated Science Lab (IceLab) at Umeå University, and the Department of Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics.

Because these processes cannot be directly observed in detail, they are often investigated using mathematical models. While powerful, such models can be difficult to understand for those outside of their immediate research field.

We thought not only about communicating our research, but also that in designing the game you learn aspects of your system that you didn’t fully appreciate

Josephine Solowiej-Wedderburn and Eric Libby proposed developing a game through the Design Build Test course — an undergraduate project-based course where students work on real-world challenges.

A game might not seem like the most immediate way to approach this complex research.

Josephine Solowiej-Wedderburn first proposed the idea to Eric after a workshop she attended during the summer of 2025 on science communication. “There was someone at the workshop that developed a game. It sounded kind of cool and fun and I thought maybe this is a useful tool to use to talk across disciplines.”

Eric Libby, an avid player of games in his spare time, immediately jumped on the idea.

“We thought not only about communicating our research, but also that in designing the game you learn aspects of your system that you didn’t fully appreciate,” Eric explained. “It’s as much of a game for us as it is a learning tool and a communication exercise.”

During the 2025 autumn term, a team of students worked to transform microbial competition and cooperation into an interactive experience. The researchers deliberately left the format open.

“I had no expectations… I didn’t know what it was going to be,” Eric said. “What they created was great.”

The result is Bacman, a multiplayer strategy game where players must survive by selecting nutrients, responding to environmental conditions, and navigating interactions with other bacteria.

In August 2025, Eric Libby and Josephine Solowiej-Wedderburn pitched their project to the Design-Build-Test students. After voting on preferred projects, students were placed into teams and began project development . For Jesper Erixon, one of the student developers, the appeal of the microbial dynamics game was immediate.

It’s nothing like the other courses… everything isn’t perfectly laid out. You have to get around these bumps and figure stuff out as you go, so you learn a lot.

“It really struck me as an interesting opportunity,” he said. “Partly as an educational tool to get more people inspired and interested in biology, but also as a research tool where you can have a simplified situation that still models some of the complex behavior we can see in research in a fun way.”

In the game, survival depends on strategy.

“You choose your bacteria… you have to be wary of the surrounding environment and the other players,” Jesper Erixon explained. Players can cooperate by using waste products produced by others or compete by securing nutrients first.

The process was not without challenges.

“None of us are game developers,” he said. “We had very ambitious ideas. We had to scale them back… but it’s a very fun and playable game, and there’s a lot of opportunity to develop it further.”

The Design-Build-Test student team presented their work to researchers in IceLab in January. They played the game together and discussed how well it captured key ideas from the research.

Presentation of the 'BacMan' Design-Build-Test student game in IceLab

ImageGabrielle Beans“I think it’s very creative… it shows how cells compete with each other over different nutrients and gives a lot of different ideas when you think about strategies,” said Sena Gizem Süer, PhD student studying bacterial stress responses, after testing the game.

Luis Jose Fernando, a PhD student with a background in hydrology, noted that the experience challenged his assumptions.

“I learned at least a little bit more about how they interact because I quite frankly know nothing about it,” he said, adding that the game was “fun to play” and “very smooth to use.”

Aswin Gopakumar, a PhD student who models ecosystem dynamics, highlighted a broader parallel between modelling and game design.

“Games cannot replicate all parts of real-life physics… we do the exact same thing with models,” he said. “Mixing those two sounds like a no-brainer.”

The Design Build Test course is structured around open-ended projects that mirror professional settings. Students from engineering physics, computer science, and biotechnology collaborated on Bacman, making creative and technical decisions along the way.

“It’s nothing like the other courses… everything isn’t perfectly laid out,” Jesper Erixon said. “You have to get around these bumps and figure stuff out as you go, so you learn a lot.”

For the researchers involved, the project showed how collaboration between students and researchers can create new ways to communicate science. It also demonstrated how translating research into another format can sharpen researchers’ own understanding of the systems they study.

Four members of the Design-Build-Test student project team sit in IceLab next to their project owners, Josephine Solowiej-Wedderburn and Eric Libby from IceLab and the Department of Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics.

ImageGabrielle BeansJosephine Solowiej-Wedderburn and Eric Libby are already considering future iterations, potentially exploring rule changes that reflect different microbial settings and introducing AI players. The team is also planning to present the game at the science festival ForskarFredag at Curiosum in September, where members of the public will be able to try it.

As Bacman continues to evolve, it highlights how interdisciplinary collaboration can make abstract research more accessible — and open new perspectives on the science itself.