The Burman Lectures in philosophy have been given annually by internationally leading philosophers since 1996. The lectures are arranged by the Department of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies at Umeå University.

C. Thi Nguyen, associate professor of philosophy at the University of Utah

Time: 14-16 oktober 2024, kl. 13.15-15.00

Place: Umeå University, Lecture Hall HUM.D.220 (Hörsal F)

Monday 14 October at 13.15-15.00PM, Lecture Hall HUM.D.220 (Hörsal F)

Abstract: Value capture is the phenomenon where individuals, and small-scale communities, adopt institutional metrics and measures as their guiding values. We go on social media for connection, but get captured by Likes and Follows. We go to school for education, but get captured by grades and university rankings. We exercise for health, but get captured by weight loss. But what might be wrong with value capture? We are social animals, and often acquire our values from our communities and culture. But there is a distinctive feature to institutional metrics and measures, that makes them particularly harmful to internalize. They are engineered to fit the demands of large-scale institutions: in particular, to fit the demand for cross-contextual portability. They resist localized tailoring and adjustment.

Tuesday 15 October at 13.15-15.00PM, Lecture Hall HUM.D.220 (Hörsal F)

Abstract: Games and institutions often use mechanical scoring systems. A game tells us exactly what gets us points; a bureaucracy tells us exactly how our productivity will be measured. Strangely, these mechanical scoring systems often inspire fun and free play in games – but in institutional life, they drain the life out of everything. Why? I offer a theory of the mechanical. A mechanical procedure is one where the procedures and criteria have been designed so as to be usable by anybody, to yield consistent results. Mechanical scoring systems perform a valuable social function: they guarantee convergence of evaluations, from those who have accepted the scoring system. To do this, however, such scoring systems need to strictly limit the kinds of criteria they can target. In games, this helps us be more fluid. But mechanical scoring systems perform a different function in institutions. Mechanical scoring systems are often used to make workers more replaceable. This deeply shapes the kinds of targets and goals that can be enshrined in institutions. And this process opens the door to the possibility of a kind of social selection process, whereby those agents who are willing to sacrifice all else, in the pursuit of higher mechanical scores, are rewarded with greater social power.

Wednesday 16 oktober at 13.15-15.00PM, Lecture Hall HUM.D.220 (Hörsal F)

Abstract: If the meanings of some terms are socially determined, and those meanings have social and political consequences, then we should engineer our terms in the light of those consequences. But this conceptual engineering shouldn’t simply be in the hands of some elite class. Rather, basic considerations of democratic inclusiveness suggest that all relevant stakeholders be involved, somehow, in the process of conceptual engineering. This is the thesis of semantic self-determination. I offer a case study: the attempt by autism advocates to intervene into the medical definition of “autism”. Meaning-determination should arise through an inclusive democratic procedure, as with any other form of self-governance. The opposite process would be one in which terms are engineered from the top-down, and imposed through a non-inclusive process. And this form of semantic authoritarianism is already occurring. It often takes the form of bureaucratic institutions and technical experts setting the meanings of official terms. Many institutional metrics turn out to be exercises of semantic authoritarianism, imposing a conception of what counts as health, well-being, value or success. And many of our folk concepts turn out to be post-bureaucratic – having already been transformed to be more amenable to large-scale institutional methodologies. What would a more democratized and localized process of meaning-setting and value-determination look like?

Learn more about C. Thi Nguyen

All interested are welcome to these lectures.

2023

Professor David Enoch, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem

Autonomy: Coercion, Nudging and the Epistemic Analogy

Lecture 1: Contrastive Consent and Third-Party Coercion

Lecture 2: How Nudging Upsets Autonomy

Lecture 3: Epistemic Autonomy May Not Be a Thing

Professor Elisabeth Camp, Rutgers University

Perspectives, Frames, and the Coercion of Intimacy

Lecture 1: From Point of View to Perspective

Lecture 2: Perspectival Framing With Pictures and Words

Lecture 3: Frames, Nicknames, and the Coercion of Intimacy

Jeff McMahan, Sekyra and White’s Professor i moralfilosofi vid Oxford University

The Ethics of Creating, Saving, and Ending Lives

Lecture 1: Abortion, Prenatal Injury, and What Matters in Alternative Possible Lives

Lecture 2: The Population Ethics Asymmetry and the Permissibility of Procreation

Lecture 3: Moral Reasons to Cause People to Exist

Professor Ingrid Robeyns, Utrecht University

Why worry about wealth?

Lecture 1: What is limitarianism?

Lecture 2: Arguments for economic limitarianism

Lecture 3. Objections to economic limitarianism

Prof. Jennifer Saul, University of Sheffield.

Race, Manipulative Language, and Politics

Lecture I: Dogwhistles, Political Manipulation and the Philosophy of Language

Lecture II: Racial Figleaves, The Shifting Boundaries of the Permissible, and the Rise of Donald Trump

Lecture III: 'Immigration' in the Brexit Campaign: Dogwhistle Terms in Complex Contexts

Jenann Ismael, University of Arizona

Determinism, Time, and Totality

Lecture I: Determinism and the Causal Order

Lecture II: Time and Transcendence

Lecture III: Totality

Karen Bennett, Cornell University.

Making things Up

Lecture 1: Building

Lecture 2: Causing

Lecture 3: Relative Fundamentality

Elizabeth Anderson, Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies at the Department of Philosophy, University of Michigan.

Pragmatism in Ethics: Why and How

Lecture 1: Why Pragmatism?

Lecture 2: How to Be a Pragmatist 1: Correcting Moral Biases

Lecture 3: How to Be a Pragmatist 2: Experiments in Living

Michael Smith, McCosh Professor of Philosophy, Princeton University

What We Should Do and Why We Should Do It

Lecture 1: "The Standard Story of Action"

Lecture 2: "A Constitutivist Theory of Reasons"

Lecture 3: "A Case Study: The Reasons of Love"

David Chalmers, Australian National University and New York University

Structuralism, space, and skepticism

Lecture 1: Constructing the world

Lecture 2: Three puzzles about spatial experience

Lecture 3: The structuralist response to skepticism

Stephen Finlay, University of Southern California

Metaethics as a Confusion of Tongues

Lecture 1: Metaethics: Why and How?

Lecture 2: The Semantics of "Ought"

Lecture 3: The Pragmatics of Normative Disagreement

Dag Prawitz, Stockholm University

Bevis, mening och sanning

Tim Crane, University of Cambridge

Problems of Being and Existence

Lecture 1: Existence, Being and Being-so

Lecture 2: Existence and Quantification Reconsidered

Lecture 3: The Singularity of Singular Thought

2009

Jerry Fodor, Rutgers University

What Darwin Got Wrong

Lecture 1: What kind of theory is the Theory of Natural Selection?

Lecture 2: The problem about 'selection-for'

2008

Susanna Siegel, Harvard

The Nature of Visual Experience

Lecture 1: The varieties of perceptual intentionality

Lecture 2: The contents of visual experience

2007

Alex Byrne, MIT

How do we know our own minds?

Lecture 1: Transparency and Self-Knowledge

Lecture 2: Knowing that I am thinking

2006

Jonathan Dancy, University of Reading and University of Texas, Austin

Lecture 1: Reasons and Rationality

Lecture 2: Practical Reasoning and Inference

2005

Ned Block, New York University

Consciousness and Neuroscience

Lecture 1: The Epistemological Problem of the Neuroscience of Consciousness

Lecture 2: How Empirical Evidence can be Relevant to the Mind-Body Problem

2004

John Broome, Oxford

Reasoning

2003

Wlodek Rabinowicz, Lund

Värde och passande attityder

2002

Kevin Mulligan, Genève

Lecture 1: Essence, Logic and Ontology

Lecture 2: Foolishness and Cognitive Values

2001

Hubert Dreyfus, Berkeley

Lecture 1: What is moral maturity? A Phenomenological Account Of The Development Of Ethical Expertise

Lecture 2: The primacy of the phenomenological over logical analysis: A Merleau-Pontian Critique of Searle's Account of Action and Social Reality

2000

Herbert Hochberg, University of Texas, Austin

Lecture 1: A Simple Refutation of Mindless Materialism

Lecture 2: Universals, Particulars and the Logic of Predication

1999

Susan Haack, University of Miami

The Science of Sociology and the Sociology of Science

Lecture 1: Social Science as Semiotic.

Lecture 2: Sociology of Science: The Sensible Program.

1998

Howard Sobel, University of Toronto

Lecture 1: First causes: St. Thomas Aquinas's 'Second way'.

Lecture 2: Ultimate reasons if not first causes: Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz on 'the Ultimate Origination of Things'.

1997

Ian Jarvie, York University

Science and the Open Society

1996

David Kaplan, UCLA

What is Meaning: Notes toward a theory of Meaning as Use

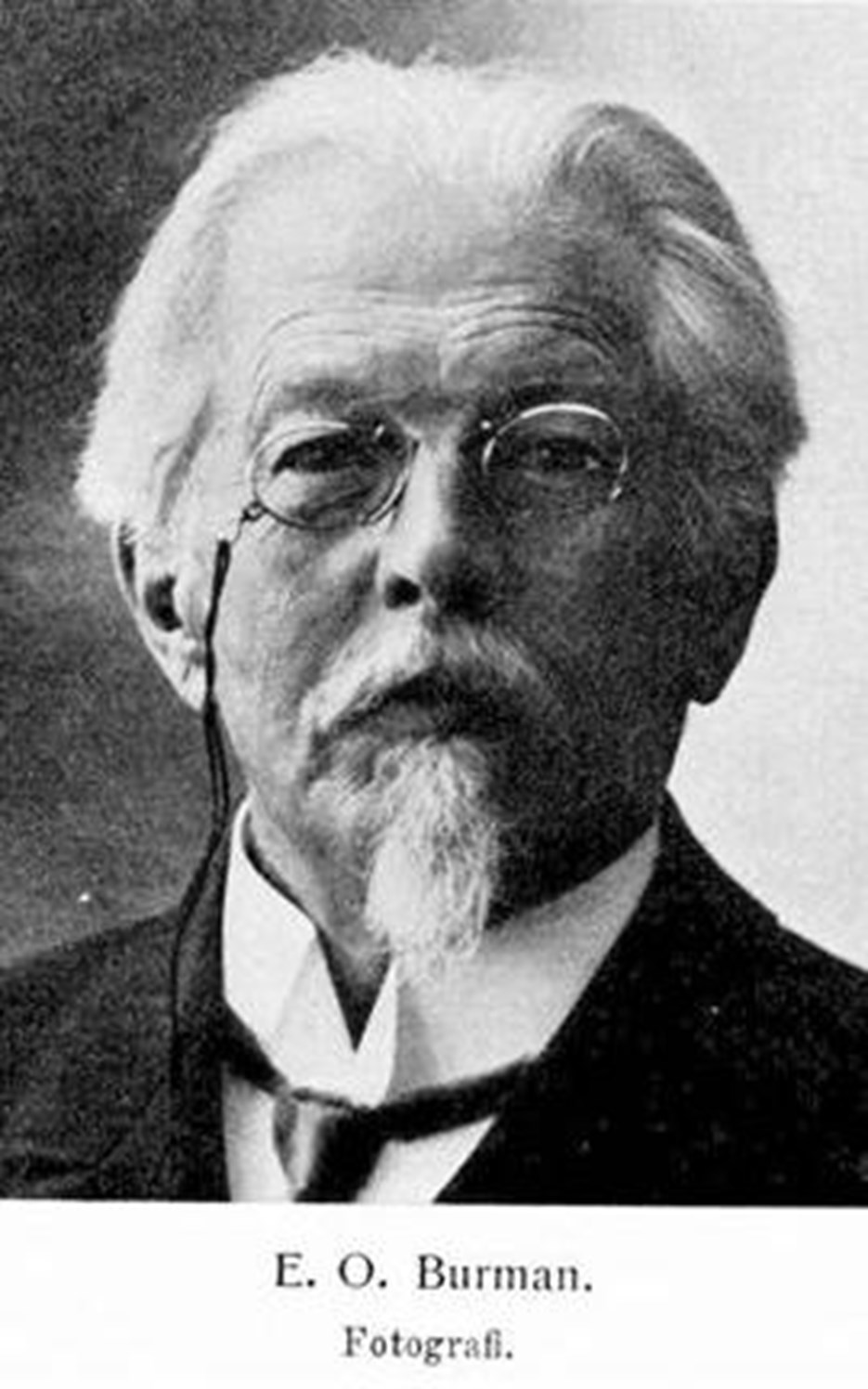

The Burman Lectures started in 1996 on the initiative of Inge-Bert Täljedal, then mayor of Umeå and later vice chancellor of Umeå University. The lectures commemorate Erik Olof Burman (1845-1929), Umeå's "first professor of philosophy".

Burman was born in Yttertavle outside of Umeå, went to high school in Umeå, and became professor of practical philosophy 1896-1910 at Uppsala University. Nowadays Burman is best known as the teacher of Axel Hägerström, who is known for his expressivist theory of moral judgments, among other things.

A longer presentation of Erik Olof Burman, written by Inge-Bert Täljedal (Pdf in Swedish)